What is Shearing

October 1, 2016

Shearing is a scissor-like process used to rough-cut materials in preparation for other manufacturing processes. In a machine shop setting, shearing is commonly done by a hydraulic squaring shear, sometimes referred to as a guillotine shear. Depending on the tooling used, shearing can be used to make straight cuts in materials including sheets, bars, and angle stock.

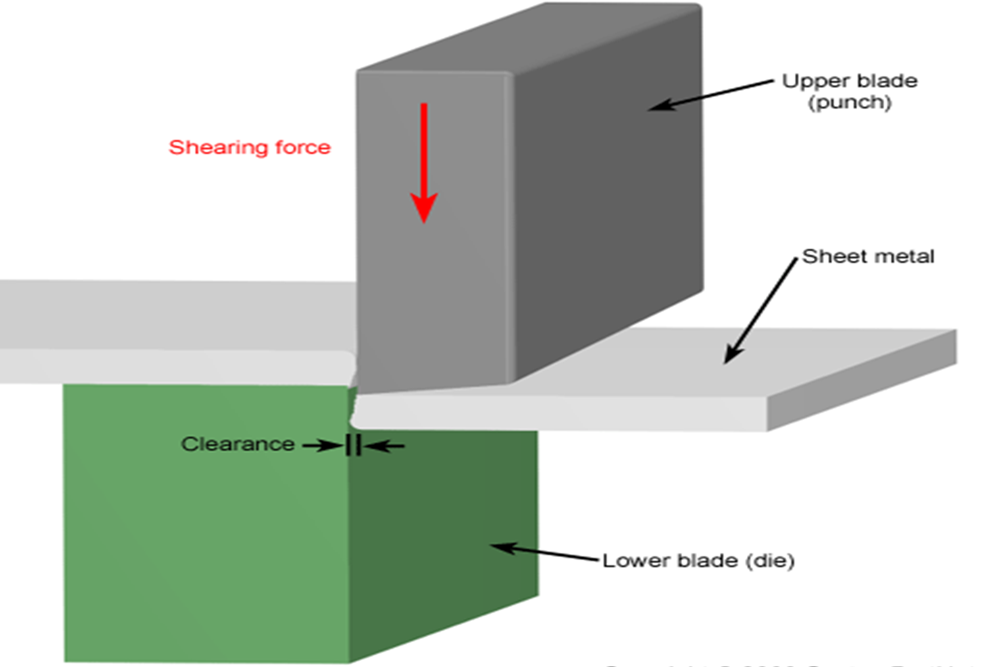

The shearing process is performed on a shear machine, often called a squaring shear or power shear, that can be operated manually (by hand or foot) or by hydraulic, pneumatic, or electric power. A typical shear machine includes a table with support arms to hold the sheet, stops or guides to secure the sheet, upper and lower straight-edge blades, and a gauging device to precisely position the sheet. The sheet is placed between the upper and lower blade, which are then forced together against the sheet, cutting the material. In most devices, the lower blade remains stationary while the upper blade is forced downward. The upper blade is slightly offset from the lower

Shearing, also known as die cutting, is a process that cuts stock without the formation of chips or the use of burning or melting. Strictly speaking, if the cutting blades are straight the process is called shearing; if the cutting blades are curved then they are shearing-type operations.The most commonly sheared materials are in the form of sheet metal or plates. However, rods can also be sheared. Shearing-type operations include blanking, piercing, roll slitting, and trimming. It is used for metal, fabric, paper and plastics.

A punch (or moving blade) is used to push a workpiece against the die (or fixed blade), which is fixed. Usually, the clearance between the two is 5 to 40% of the thickness of the material, but dependent on the material. Clearance is defined as the separation between the blades, measured at the point where the cutting action takes place and perpendicular to the direction of blade movement. It affects the finish of the cut and the machine's power consumption. This causes the material to experience highly localized shear stresses between the punch and die. The material will then fail when the punch has moved 15 to 60% of the thickness of the material because the shear stresses are greater than the shear strength of the material and the remainder of the material is torn.

Two distinct sections can be seen on a sheared workpiece, the first part being plastic deformation and the second being fractured. Because of normal inhomogeneities in materials and inconsistencies in clearance between the punch and die, the shearing action does not occur in a uniform manner. The fracture will begin at the weakest point and progress to the next weakest point until the entire workpiece has been sheared; this is what causes the rough edge. The rough edge can be reduced if the workpiece is clamped from the top with a die cushion. Above a certain pressure, the fracture zone can be completely eliminated. However, the sheared edge of the workpiece will usually experience work-hardening and cracking. If the workpiece has too much clearance, then it may experience roll-over or heavy burring.